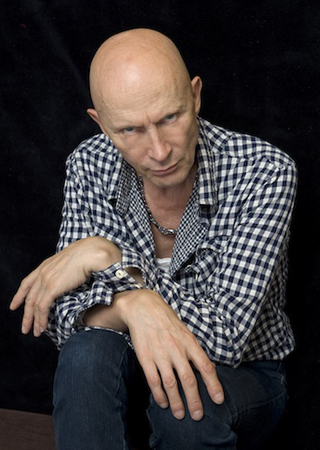

David Lynch: The Road to Hell

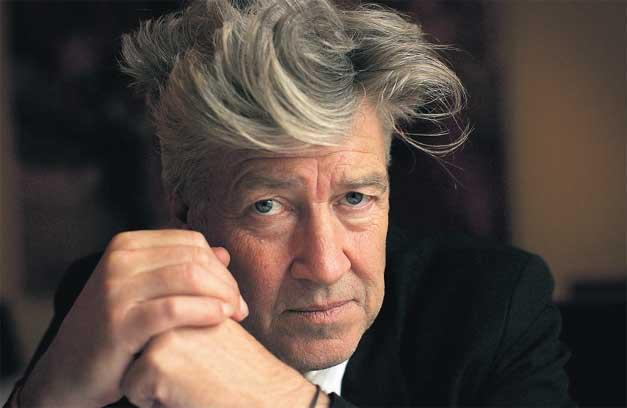

David Lynch

David Lynch, reticent purveyor of wall-to-wall cinematic weirdness, is back with ‘Lost Highway’. It may well be his oddest offering yet, upping his ante on the even his last film, 1992’s reviled ‘Twin Peaks:Fire Walk With Me’. And no he doesn’t want to talk about it.

‘Oh, my,’ says David Lynch, as he walks into the Paris hotel suite. ‘Look at you all lollygagging around.’

Lollygagging?

Stranger still than Lynch’s time-warp vernacular is the way he invests the word with the shocked awe a ten-year-old might display on interrupting his older sister shagging the college football team.

Now, it might seem slightly unusual to find an assortment of film PRs together with Lynch’s own 14-year-old son, your humble scribe and shoestring video humorist Adam (or was it Joe?), all sprawled on the bed munching snacks and watching the cult duo’s hysterical spoof ‘Toytrainspotting’, but more Bacchanalian orgies have been known.

And it’s a bit rich coming from a man responsible for some of the most shocking scenes ever committed to film.

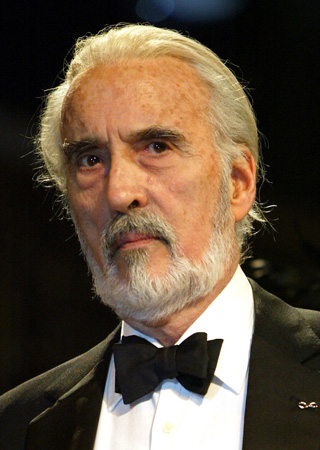

Lynch’s debut feature, ‘Eraserhead’, is so called because the hero gets decapitated and his head made into pencils. His stab at a blockbuster, ‘Dune’, features a bloated, pus-faced pervert, Baron Harkonnen, pulling out plugs attached to the hearts of his boy victims at the moment of orgasm. ‘Blue Velvet’ starts with a severed ear and gets much worse, and in ‘Twin Peaks’ he turned supernatural evil, serial-killing and incest into prime-time soap. In ‘Wild At Heart’, he cut graphic scenes of torture only after a hundred people had walked out of a test screening. But mostly, he uses the unseen, a heightened banality coupled with an extraordinary use of sound, to create a terror of the unknown. ‘The X Files’ would never have happened without ‘Twin Peaks’.

So it’s with some anticipation that the film-going public is lollygagging around, awaiting his first movie in four years, ‘Lost Highway’. It is extraordinary, almost a compendium of Lynch’s obsessions. It’s also near-incomprehensible. Not so much a ‘whodunnit’ as a ‘whatthefuck-wasallthatabout?’, it still gives the impression that behind the string of striking images there might just possibly be a narrative thread. I’ll try to help you out on that score, but first, there’s the problem that an interview with David Lynch is famously as mysterious. He won’t talk about his private life, and he won’t talk about his work.

Since neither of us are football fans, that leaves us, for the moment, with his diet tips. So David, I ask, emboldened at being poured some Damn Fine Coffee by the man himself. Find any good doughnuts in Paris?

‘I’m off the doughnuts,’ is the response that will shock ‘Twin Peaks’ fans to the core. ‘I’m off bread and potatoes. On a diet, yeah. Of protein, vegetables, fruit, many good things. But you can’t combine it with things that trigger your insulin level to go up. When your insulin level goes up, it forms a hand, and the hand grabs the fat, and puts it in your body.’ Miming this, he makes it so sinister that I haven’t eaten a doughnut since. He’s lost 22 pounds; quite something from the man who used to call sugar ‘granulated happiness’.

Trailer for Eraserhead

Jennifer Lynch subsequently wrote and directed ‘Boxing Helena’, about a woman whose limbs are cut off one by one by her adoring boyfriend to keep her by his side. Kim Basinger lost a multi-million-dollar law-suit after walking off the project. Money well spent. Jennifer was quoted as saying that her dad found the film offensive (yes, it was that bad), something Lynch denies: ‘But it should perhaps have been a small film that found its way. The way it turned out, it just set her up for a fall.’

Which is just where Lynch himself is often headed. Just two years after ‘Wild At Heart’ was the toast of Cannes, winning the Palme d’Or, his ‘Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me’ was booed and reviled. At the same time, his second attempt at TV, ‘On The Air’, was pulled after a few painfully unfunny episodes. Can ‘Lost Highway’ put him back on the map?

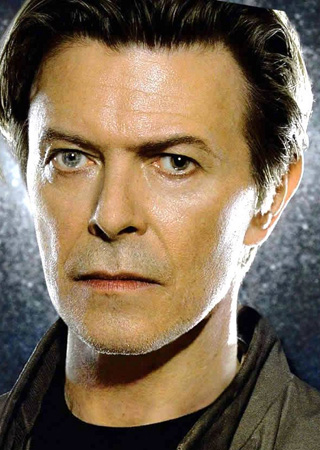

Typically, Lynch leaves mundane cartography to reviewers and the public to worry about. Instead, he’s driven right off the road to make the darkest, strangest film of his strange and dark career. The first third is slow and sombre and pregnant with menace, as Bill Pullman and Patricia Arquette, married but separated by invisible walls, receive anonymous videotapes each morning that penetrate further and further into their house. Then we’re in another film entirely as Bill Pullman, on Death Row for the bloody butchery of his wife, metamorphoses in a police cell into young Balthazar Getty why, we never really know and is released by his baffled gaolers into a bright, ’50s-styled world where Patricia Arquette is also transformed, into a blonde-haired gangster’s moll who sucks him into danger, lust and finally murder again.

Things are further confused by a man known only in the credits as Mystery Man, Lynch’s most disturbing creation since Dennis Hopper in ‘Blue Velvet’, who also has a habit of being in two places at once. The film ends, in an infernal time-loop, exactly where it began.

That’s about all the plot that can be described. Along the way there’s hot sex and distant sex; a head-wound of heroic proportions; and a gratuitously weird but very funny sequence in which crime boss Robert Loggia pistol-whips a tailgaiting driver while lecturing him on the highway code. If you can be arsed, you can spend a good couple of hours with your cinema date debating what on earth is going on. Alternatively, you can pick up what tips you can from the following…

It’s good to talk?

Try and ask Lynch anything about what the film means, and he’ll say things like: ‘It’s good to talk about some things, and some things it’s good not to talk about. I love more than to intellectually understand something, to feel an understanding of something.’ Right. Thanks a lot, Dave. So if you won’t say anything, here’s what we’ll do: I’ll tell you what I think this movie means, and you can tell me if I’m hot or cold. Okay? Okay.

Here goes the big one. Kyle MacLachlan once said that, when playing Agent Dale Cooper, he imagined him as Jeffrey from ‘Blue Velvet’ grown up. Maybe the Bill Pullman character isn’t a different person from the Getty character; maybe he’s just the grown-up version? That’s why the second half seems so ’50s, because it indicates a shift back in time. And while Getty and Jeffrey both lusted after these doomed mystery women, Pullman has actually married her, and found that life with her isn’t all it’s cracked up to be, because marriage is sometimes a matter of distance rather than coming together.

Lynch nods like a dog in a car’s back window, almost rocking his head off during the bit about marrying the mystery woman. Is it my imagination, or are we both thinking of his now terminated relationship with Isabella Rossellini, whom he met while casting the part of Jeffrey’s doomed siren in ‘Blue Velvet’? But all he’ll say is: ‘Very good.’ So, does that mean warmish? ‘Yes, that’s very good.’ But you’ve nothing to add to that? ‘No.’ Jesus!

Back to split personalities. There’s an old proverb about how the devil enters the world through a mirror… (Lynch looks blank.) In ‘Twin Peaks’ death is literally through the looking-glass, where people talk backwards. All your films deal with the duality of good and evil, often fought out internally. The Mystery Man in ‘Lost Highway’ seems, like Frank Booth in ‘Blue Velvet’, a straightforward embodiment of evil, the dark side. (Lynch cocks his head like a bird to indicate ‘cold’.) Um. Or is he a Creature From The Id, summoned up from Bill Pullman’s subconscious? (Lynch nods at last.) Is that warm? ‘Yeah.’

One bit I really liked was where Getty transforms back into Pullman, when they’re making love in front of the car headlights in a bright white light, like at the end of ‘Fire Walk With Me’ where the angel descends. So is this a kind of angelic visitation? (He’s nodding, saying uh-huh, but as if he’s expecting more.) So I don’t know where that goes exactly… (Lynch laughs, and doesn’t help out.)

You’ve said before you believe in reincarnation. Is it anything to do with Karrna, the wheel of life, with rebirth? ‘It could be.’ Then, evasively: ‘You know there’s, ah, all sorts of symbols of beautiful transformations, like the cocoon into the butterfly. So it makes you wonder, you know, what is this transformation we’re going through?’

Lynch is trying to stray off the subject, which means I’m onto something. So there is life after death? ‘Aaah, I think so. I think it’s a continuum.’ So what’s it like? (Laughter.) Not a room with red curtains and people talking backwards, then? ‘That would be kinda beautiful to me.’

But the black, depressing thing about ‘Lost Highway’ is that Bill Pullman can never die. He’s trapped in this time loop, doomed to repeat his murders and mistakes for ever and ever. ‘Well, maybe not forever and ever, but you can see how it would be a struggle. Yeah, that’s it.’ (Lynch looks uneasy. He’s given away too much!)

So it is that Buddhist notion of reincarnation, that you can only get off the wheel to Nirvana after thousands of years? ‘Exactly.’ So there is light? Pullman could be released if the film carried on? ‘Oh yeah. Sure. It’s a fragment of the story. It’s not so much a circle as like a spiral that comes around, the next loop a little bit higher than the one that precedes it.’

Pryor engagements

So there you have it. Or not, depending on which particular red herring you’re inclined to fish from what Lynch thinks of as the ‘ocean of ideas’. But hey! There’s a million stories in the naked city that is David Lynch’s mind; it may be even he doesn’t know which is the true one. When he paints, apparently, he paints with his eyes closed…

But I still have to pin Lynch down on a couple of things that make people doubt his motives. What about including Richard Pryor, the great comedian currently laid low with muscular sclerosis, in his gallery of grotesques as a wheel-chair-bound garage-owner? For the first and only time, Lynch gets quite narked. ‘Now why should I want to make fun of Richard Pryor? And why shouldn’t he be in the film? Richard Pryor is a great guy. He’s in a wheelchair, and he can’t play a huge role, but I really wanted to work with him. I saw him in a show, and I fell in love with him. He was just talking about himself and his life, and I said I really wanted to work with this guy. He did the scripted scenes, and then I put him on the phone in the office of the garage, introduced a mental concept, and let him go for nine minutes. He was amazing. A fragment of that is in the film. That’s the kind of thinking… it’s really sick and twisted. It’s really them that are imagining these things, so they’re the sick and twisted ones just to come up with that concept.’

Equally sick and twisted, according to him, are the accusations of misogyny and pornography that have dogged him ever since ‘Blue Velvet’. I have up my sleeve a copy of a 1988 book of ‘film noir’ reviews by Barry Gifford, author of ‘Wild At Heart’ and co-scripter of ‘Lost Highway’ itself, in which he describes ‘Blue Velvet’ thus: ‘One cut above a snuff movie. A kind of academic porn. I can never imagine things as depraved as those that occur here, and I’ve always thought I could get pretty low in that department. Pornography, as such, simply bores me. So this movie isn’t for me, yet it seems somehow important and worth discussing.’ With friends like that, who needs enemies?

‘He says it’s not for him?’ Lynch responds when I read it to him. ‘I’ll never work with him again’. He’s joking,of course…

‘Lost Highway’ will certainly reopen the debate. It features Patricia Arquette fucked from behind and made to strip at gunpoint, only to discover that she enjoys it. Lynch would counter that that’s just the way the character happens to be. Certainly, his male characters are even more passive, and no less sexually screwed up. It’s more that Lynch’s own sexuality was imprinted in the ’50s, with his fetishistic fondness for sweater girls in high-heeled shoes with lipstick like a gash of blood. It does seem suspicious that a man who ‘stepped out with Ingrid Bergman’s daughter for several years should also have cast Natalie Wood’s daughter in ‘Lost Highway’ and, it must be said, dressed her in a tight ’50s sweater which is conspicuously removed in the back of a car. Was it because he used to fancy her mum?

‘I fancied Natalie Wood, sure, but that’s not why Natasha was hired. I met her and suddenly realised I’d met her 18 years before. I didn’t actually see her then, but her mother was eight months pregnant. It was when I first went to the American Film Institute, and they had a big party one evening, and Natalie Wood came out on the verandah.’

So it’s back to your cycle of life and birth ?

‘Exactly right.’

Later, I travel to the exhibition of Lynch’s recent paintings and photographs at a swanky Paris gallery. The canvases mix words and images, wood and insects buried under paint, but the photos really disturb. Dozens of close-up snaps of high-heeled shoes, legs, bottoms, breasts; women’s body parts disassociated from their faces. There’s one full-length shot of a girl lying on a sofa, and then, lastly, the sofa with no girl, only a puff of smoke. Magic? Or abduction? The display reminds me of something, and it takes a while to work out what: it looks just like the wall of a serial killer that bit in the movies when the police burst into his bedroom just before he’s about to make his final kill elsewhere…

Perhaps it’s just as well that Lynch continues to make his extraordinary movies.

‘Lost Highway’ opens on Aug 22

Er, well, it’s kind of, er…’

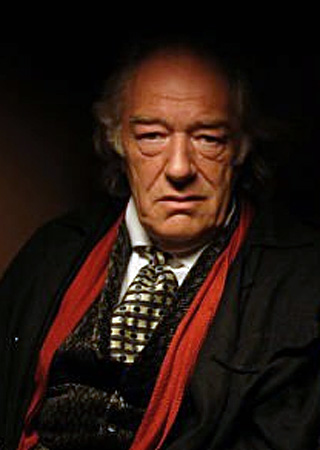

On the couch with David Lynch

David Lynch seems like the only man in Hollywood never to have had psychoanalysis. “I went one time, and I asked him if it might affect my creativity. And he said, ‘David, I have to be honest with you, it could.’ And I said, ‘Well, I’m happy to meet you, but I have to go.” Having witnessed therapy-junky John Cleese’s comedy diminish as his happiness increases, one can sympathise. However, certain Lynchian motifs recur so obsessively that we’re dying to know what they mean. So come on Dave, lie back on the couch and tell me the very first things that come into your head when I say these words:

1) FIRE There’s Lynch’s trademark close-ups of cigarettes; the blaze that haunts Wild At Heart. Fifteen seconds elapse. “Well, it’s… It’s kinda…. It means different things in different situations. When I just think about fire, it’s so pure, I don’t think about anything else.” And then, shockingly; “When you said it, I was picturing being in it.” Your first student short was apparently of heads throwing up and catching fire. “It was the reverse, actually. But the elements water, earth, air and fire it’s no accident that we really like those things,and things get reduced down… Fire is so magical. There’s a texture to it that occurs nowhere else. And controlling something like that… It wants to get bigger if it can, and then you’re very worried that one will go out! With me, I always think about magic, the unexplainable.”

2) JAZZ Lynch works very closely with his composers, though it must be said, Bill Pullman in Lost Highway is the least plausible jazz saxophonist ever seen. Hardly any pause. “Freedom. It’s like no constraints, an opening, and then barriers going away and lifting and breaking and experimentation and…it’s like attempting for something.”

3) THE BRAIN Each Lynch film out-grosses itself on the brain front; Eraserhead’s title speaks for itself; The Elephant Man is killed in his sleep through the sheer weight of his head; Blue Velvet has the shot cop briefly still standing, brains exposed, like a faulty electrical appliance; in Wild At Heart Sherilyn Fenn wanders about holding her brain in place while asking if anyone’s seen her hair brush; Lost Highway tops the lot by burying a glass coffee table in a man’s cranium. “Well,um…” Nineteen seconds go by. “The brain is just like a plate but the nervous system and the mind is, ah….” Twenty-seven seconds silence as he furrows his brow comically like a boy at examination time, “It’s the thing that traps us and ultimately frees you.”

4)THE BED In “The Grandmother,” Lynch’s best short, a lonely boy grows a grandmother from a plant on his bed, on which she later dies; Wild At Heart contains heroic fucking scenes. Complete silence for 48 seconds. Then Lynch giggles like a schoolboy to whom one has whispered the word “sex.” “It’s sort of like… It’s used for many things, but it really is a closeness to death.” Pause. “And birth, too.”

5) RED CURTAINS The afterlife/limbo of Twin Peaks; in Lost Highway the camera moves over red curtains like a spaceship exploring a strange planet. Immediate response. “Curtains are both hiding and revealing. Sometimes it’s so beautiful that they’re hiding, it gets your imagination going. But in the theatre, when the curtains open, you have this fantastic euphoria, that you’re going to see something new, something will be revealed.”

6) THE OUTSIDE Where Jeffrey finds the severed ear in Blue Velvet, the woods where all the weirdness happen in Twin Peaks; the Lost Highway itself. Lynch was terrified of the outdoors as a child. Immediate response. “Right, I did have a period of that. I really like captured space. Even great vistas are okay because I see some edge. But the word outside, it’s uh, too random. I lose a bit of control with that word.”

And yet your dad worked for the Department of Agriculture. “My father was a woodsman, yes. And wood has played a huge role in my life. So I like building things out of wood, I like chainsawing, I like the smell of the wood, I like the look of a tree, particularly my father’s favourite tree was the Ponderosa Pine. The wood is… everything all the fairy tales made you feel.”