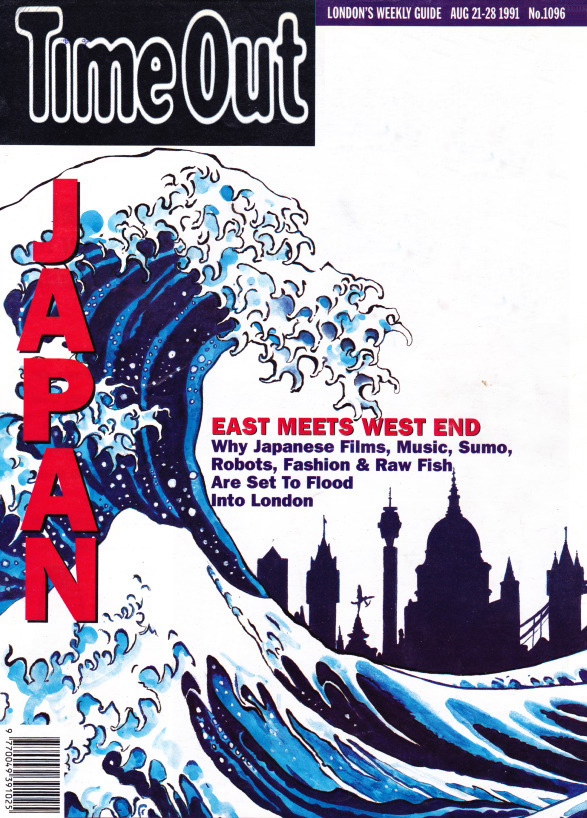

Japan Festival

Time Out: Japan Cover

(Time Out, 1991)

RAW FISH, Mount Fuji, geisha girls. Sumo wrestling, samurai warriors, sadistic game shows. This is what Japanese culture means to the West; but to Japan, Western culture is everything. Baseball is the national sport; Schwarzenegger dominates the cinemas; Reagan nets $10 million for lecture tours; rap and acid house fill the clubs; Madonna sells out the stadiums; whisky is preferred to sake; Western musicals are all the rage.

Does a uniquely Japanese culture exist anymore? Even the Japanese are worried it doesn’t. Strangely, we in London will soon be better placed to find out than they. Brace yourself for the Japan Festival: four years in the planning, £15 million in the spending, with 120 events spread over four months. Taking in Kyoto gardens and Kabuki theatre, Sumo and cinema, a weekend festival in Hyde Park and the V&A’s biggest exhibition this century, it aims to ‘foster a greater cultural understanding between the two nations’ — and give us a great time doing so.

However, many Japanese have complained that the festival relies too heavily on traditional art forms. ‘It’s like having an England Festival with Morris dancing, coracle-making and madrigal-singing,’ said one London-based student. While that’s not entirely fair — the festival’s opening play, Ninagawa’s 1988 ‘Tango at the End of Winter’, is an honourable exception — it does demonstrate the inherent problem: is there a modern Japanese culture, or are they just Americans in disguise?

Old Kyoto, new Shinjuku

At the Ryoanji Temple in old Kyoto there is a Zen garden. Lovingly maintained since the fifteenth century, it consists of nothing more than 15 rocks set into white gravel. The bigger rocks are covered in moss at their base, suggesting a Pacific island in miniature, and the gravel is carefully raked around them into concentric circles, suggesting ripples, as if the rocks had just surfaced from the sea. It’s one of the most exquisite, perfect things I’ve ever seen. ‘Japanese people don’t come here very much,’ says the guide sadly. ‘They find it rather sombre.’

In the Shinjuku district of Tokyo, amid neon signs hundreds of feet tail, there are multistorey video arcades on every corner. Half the games, predictably, are the Beastbusters shoot-’em-up variety; the other half, a digitised version of the centuries-old game Mah-jong. A typically Japanese touch is that the video rewards each win by divesting a compliant, computerised girl of another article of clothing.

Though the Japanese perceive the essential conflict in their society as between them and the US — witness the fact that the recent American book ‘The Coming War With Japan’ sold out its 40,000 print run in Tokyo within a week — the real conflict is more universal: simply, that between old and new. In a way, it’s the same thing. When Commodore Perry’s gunships steamed into Edo in 1853, two centuries of isolation ended, forcing Japan to adapt or perish. When Fat Boy dropped on Hiroshima in 1945, ending the newly industrialised nation’s dreams of military conquest and ushering in seven years of American occupation, Japan had the lesson driven home again: if you can’t beat ’em, join ’em. Japan is a hothoused nation, forced to develop at an accelerated pace like some strange experiment in genetic engineering. The result is that the Japanese consider themselves by turns the greatest nation on earth, and the least culturally developed.

Jesus Christ Superstar

In an attempt to shed some light on this cultural schizophrenia, I went to see a Japanese language version of ‘West Side Story’. Performed by the Shiki Company, which owes its status as Japan’s pre-eminent theatre company largely to the money made from Western musicals like ‘Cats’ and ‘Phantom of the Opera’, its choreography was breathtaking. It was such a faithful re-creation of the Broadway hit, in fact, that I wondered why they bothered. My suggestion that they could at least have re-cast the rival gangs not as New York WASPs v Hispanics, but Tokyo delinquents v Koreans, met first with shocked silence, then typical Japanese doublethink. ‘That makes no sense. There is no racial prejudice against Koreans.’ Yeah, right.

Keita Asari, who still runs the Shiki Company almost 40 years after founding it, is well aware of the contradictions, but proud of beating the Americans at their own game. ‘It’s true,’ he smiles. ‘We do dance it better. And in a sense that symbolises the state of Japanese people right now. To an extent we are copying the West, and audiences have the notion that anything Western is wonderful, and traditional things are obsolete. But then if we can do it better… And we are going beyond copying. We have gained the power to use the form of Western-style dramas to express our own modern life.’

‘Ri Koran’, for instance, an original musical by Asari, recently dramatised the hushed-up history of Japan’s wartime activities in China. It was a sell-out success to match any of the Shiki Company’s Western imports.

Unfortunately, in common with much of the Festival, the Shiki Company has chosen to play it safe. Instead of bringing over ‘Ri Koran’, it will be performing its own version of ‘the musical with the longest-ever run in London’: ‘Jesus Christ Superstar’. With Jason Donovan currently packing them in for ‘Joseph and the Amazing Technicolor Dreamcoat’, it’s a timely revival. But in Japanese? What does this nation of Buddhists and Shinto-ists know about Christ?

Asari explains: ‘Christianity came to Japan 400 years ago, and was accepted by the authorities. But at certain points after that they became afraid of Western culture and banned it. Those who refused to change were crucified — hundreds in Nagasaki alone. When Christ is put on the cross at the end of the musical, I wanted it done in the same way as to the Japanese in the past.’

His version makes that point by incorporating traditional Kabuki techniques — white-washed faces, a stage made up of seven movable drays or wagons, a mix of electric guitars and shakuhachi flutes, and an outrageously, unforgettably camp King Herod in a blue fright-wig that draws on Kabuki’s famous onnagata (female impersonators). The production is a stunning attempt to fuse Western and Japanese theatrical forms and carries the blessing, in a rare moment of conciliation, of both Rice and Lloyd-Webber. All the same the result, to British eyes, is slightly misguided: the direction gives little chance to show off the Shiki Company’s dance skills, and the tattered biblical rags and painted faces are disturbingly reminiscent of the rock band Kiss.

But while ‘Jesus Christ Superstar’ proves that traditional theatre still has relevance today, London will also play host to the real thing: the Grand Kabuki of the Shochiku Company. If you want to know about Japan’s cultural roots, and how they affect modern Japan, this is where to look.

Noh theatre at all

Kabuki began in 1603, influenced by the elitist and incomprehensible Noh court dramas (George Bernard Shaw once quipped ‘The Noh Theatre is no theatre at all’) and the more populist Bunraku puppet shows. It suffered a minor hiccup when the Shogun, worried at off-stage indiscretions between male and female actors, banned women; and another hiccup a few years later when, worried about offstage indiscretions between the men and the boys who now played women, the Shogun banned boys too. But basically it has been Japan’s preeminent form of drama for centuries.

On a typical evening, I was treated to five hours of Kabuki interrupted by two intervals. It’s not easy, at first: the Japanese themselves can’t understand the archaic dialogue which, in an English frame of reference, would be closer to Chaucer than to Shakespeare (in London, the audience will receive a simultaneous translation on headphones). Jetlagged to the point of hallucination, I began to hear the stylised, sing-song growls as English sentences, scrawled in my note-book in a sleepwalker’s shaky hand for posterity: ‘Mr Ridley taunts you with no cause,’ says a Samurai warrior, with surprising topicality. ‘Screw in this totally modern model of a motorcar,’ ripostes his adversary. The death scenes last half an hour. With her final breath, the suicided heroine intones, deathlessly, ‘Here the drinks are very expensive. Would I were in Martinique, paying no more for the same.’

After cold, sweet coffee from one of Tokyo’s ubiquitous vending machines, the next two acts made more sense. For the most part, words are superfluous. The sets are spectacular, from the simplicity of a cherry tree showering its pink petals in act two to the undreamt of mechanical complexity of act three, when two boats bob around in a ‘lake’ before rowing gracefully down a ramp right through the audience. The painted faces convey a greater subtlety of emotion in a tilted profile and raised eyebrow than all the theatrics of a Glenda Jackson; the dances have a precision that only decades of training can give; and it’s not until you remember, half-way through, that women have no place in Kabuki that you realise these are in fact onnagata, the famed female impersonators.

The next week, I was ushered into the dressing room of Kankuro, at 36 one of the youngest and most popular Kabuki actors, from whom I hoped to discover how Japan could reconcile the old and the new. The room itself was a metaphor: tatami mats and television, yukata gowns hung up alongside suits. But though Kankuro hosts a weekly chat show on Channel 6, he uses his slot to persuade viewers of the need for tradition, for the old arts. He needs little prompting: ‘One thing I find disheartening is to hear so many disparaging comments about us from Westerners; they just say “Fuji! Geisha girls!” But the younger Japanese too are very ignorant. If you ask them what is a Geisha, they say a prostitute. The Japanese too are turning into idiots, like Westerners.’

Not much reconciliation there. But then Kabuki actors are like nobility in Japan: schooled in deportment, in the traditional instruments, songs, dances and speech, lessons handed down from father to son. Kankuro, who was a star even as a child, is the eighteenth successive generation of his family to become a Kabuki actor; his two small sons, whom I saw perform, have a stage presence beyond their years. They will be joining Kankuro on the South Bank next month.

The family connection doesn’t end there: Kankuro will be performing the Lion Dance for which his grandfather was world-famous. Kneeling on the tatami mat, the yakuta gown slipping open to reveal very Western Y-fronts, he shows me a family album: pictures of Granddad with Douglas Fairbanks, Chaplin, Pavlova; Olivier presenting him with the sword he’d used in ‘Hamlet’. He almost made it to the London stage, but World War II got in the way. ‘I’ll be fulfilling his dream,’ says the dutiful grandson.

And here, suddenly, is another key to understanding Japanese culture: the family. It’s well known that a large part of Japan’s economic success derives from companies making themselves into a surrogate family for their employees; a worker is liable to see more of his boss, even in a social context — the piss-up after work, the weekend golfing — than of his wife. But this sense of family also provides a sense of continuity, of common purpose to the arts, evident in everyone connected with the festival I talked to. Asari’s Shiki Company, with its pension plan, is like a family. In Kabuki outsiders are almost unknown, because the best actors are those who started alongside their fathers at the age of three. The influential film programmer Etsuko Takano (of whom more later) was given a cinema to manage by her brother-in-law. Mr Iowe, who is heading a team to re-create a Kyoto Garden in Holland Park, comes from a 200-year-old family of garden architects. Sumo wrestlers live in ‘stables’ where everyone eats, sleeps and trains together: a surrogate family. Only the most senior ones can get married, and move out.

Even teenage rebellion is a communal activity — witness the thousands of youths who gather in Yoyogi Park of a weekend, dressed in identical James Dean uniforms! The few times I was allowed out without a guide, the fact that I had made my own way to an appointment was met with amazement; not so much that I had found the place (Tokyoites are forever getting lost in their own city), but that I should wish to travel alone.

And yet a true artist is by nature solitary, developing his or her own unique vision at odds with the common consensus. How can the Arts in Japan fail to be anything more than a pastiche, borrowing elements from the West, from their own traditions, but developing nothing new?

Keita Asari rejected this theory out of hand. ‘It’s no different in Japan to the West: people who are creative do it alone. Look at Hokusai [the printmaker responsible for ‘The Wave’, whose work will be celebrated at the Royal Academy of Arts in November]. He was stubborn, he would only paint when he felt like it; he was always drinking sake. We in Japan are always yearning for this type of person, whom we consider genuine artists.’

That may be so. All the same, to Western critics, modern Japanese fine art appears derivative; their greatest classical musicians play to perfection, but lack soul; their rock stars would find the Eurovision Song Contest outrageously wild; their modern drama is, as Asari himself admits, in its infancy. (Ninagawa, whose ‘Tango at the End of Winter’ is the first major play of the festival, is an honourable exception.) And so we return again to the question: have the Japanese a unique culture for today, or just a glorious tradition?

A resounding yes

In two fields at least, the answer is resoundingly yes. The first is manga, the comics which make up a third of Japan’s yearly publishing output; though they are not represented in the Festival because no sponsorship could be found, a manga exhibition will be held at the Pomeroy Purdy gallery in October. The second, better known to those who visit London’s repertory cinemas, is film.

Here cross-cultural fertilisation has worked a miracle. Kurosawa, for instance, owes as much to John Ford’s Westerns as to Kabuki, but his samurai films then heavily influenced the Spaghetti Western of the ’60s — ‘The Magnificent Seven’ and ‘A Fistful of Dollars’ were direct lifts — as well as European directors such as Wajda (witness ‘Ashes and Diamonds’). And anyone who saw Itami’s ‘Tampopo’ or Otomo’s ‘Akira’ will know that Japanese films still have much to teach us.

The Japan Festival is highlighting the rich history of Japanese cinema with a season of classic wide-screen movies at the NFT, and the biggest ever Japanese retrospective at the Barbican. Entitled ‘The Big 50’, it will screen in chronological order the work of 50 different directors from 1931 to the present day and include the premiere of Kurosawa’s latest, ‘Rhapsody in August’. The season has been criticised, like the rest of the festival, for concentrating on past glories. But it also points up the modern malaise in the Japanese film industry: as with the British, it’s stronger on quality than quantity.

Etsuko Takano, who programmed ‘The Big 50’, candidly admits that ‘Japan is rather behind in culture, especially in the movie field. We need good education — we don’t have any courses for film; subsidies should be encouraged, film centres strengthened. Japan is about to be born again into a new phase; but people don’t know what to do at this changing point. We need ideas, we need to support Japanese movies and stop just buying from America.’

It’s a litany which will be familiar to us Brits; but Takano has already done more than most. Over 60, with water on the knee, she is still a tireless globe-trotter and a conversational juggernaut who devotes her whole life to popularising film. In 1974 she started Japan’s first repertory cinema, at Iwanami Hall, showing European and Third World art movies as well as forgotten Japanese masterpieces. Now, it’s said, the 240-seat cinema has become so influential that a favourable opening there can guarantee nationwide distribution. One of her protegees is the documentary filmmaker Haneda, the only woman represented in ‘The Big 50’. Her latest offering, a three-hour film about ageing, got record attendances.

‘People thought I was crazy to do it, but it was an epoch-making event. The queues stretched round the block, people thought there had been an accident! After that it was shown in 600 different cinemas.’

And here, suggests Takano, lies a simple remedy. You could almost double your film-making power by letting in women. Everyone else I asked about the inherent sexism of Japanese society refused even to contemplate the question; one interpreter was so outraged that she answered the question herself without relaying it. But for Takano, who was thwarted in her own ambitions to direct in the ’50s, it is deeply rooted in Japanese culture.

‘In Japan, there are no career women directors in drama, only documentary, which is less threatening. In China, the Philippines, Sri Lanka, they have women directors. So at Iwanami Hall I am trying to use a lot of women and encourage them. But in a way, this is a good time for women, because we are only given a chance when things get really bad — the Leader of the Opposition Party, Ms Doi [who has now resigned], came out when the party was in a terrible state. If we can use this chance, we may be able to improve things.’

Given that Japan’s few businesswomen still speak in a simpering, high-pitched voice so as not to offend their male colleagues, we won’t hold our breath. Nevertheless, Takano is proud of inaugurating an International Women’s Film Week to tie in with the annual Tokyo Film Festival. ‘Everyone said to me, “Why do you want to do this? Women will never be able to do anything good.”’ It was a hit. She shows me the glossy brochures, but they only reinforce the impression that ‘feminism’ is a word with no Japanese translation. They are unpromisingly titled ‘Feminine Brilliance On Screen’ and, the crowning irony, the only advertisements inside are for perfume.

One glimmer of promise, however. According to Takano, ‘Now in Japan people are saying that the will for culture and the will for the economy should be the same size; and if they’re not, we’re proceeding in the wrong direction.’ The ex-chairman of Toshiba, who has helped raised funds for the festival in Japan (twice the sum donated by English companies), confirmed her statement. If Japan is to bend its iron will towards developing the arts as it has towards developing its technology, by the twenty-first century there will be no more arguments about a ‘unique Japanese culture’.

But for the moment, that question remains. Back to London for the final piece in the puzzle. ‘Visions of Japan’, the mammoth exhibition for which three rooms are currently being customised at the V&A, aims to present everything that is most vibrant about Tokyo. Masterminded by the one of the world’s most exciting and influential architects, Arata Isozaki, it presents past, present and future: from a full-sized temple and tea house, to a room filled with the sights and sounds of a contemporary Japanese city (including Godzilla’s Corner, massage machines, a vending machine labyrinth and a ‘sound shrine’), to a future vision of an electronic paradise. The festival’s chief concession to modernity, it’s an overwhelming, confusing, fascinating mish-mash, not unlike Japanese culture itself.

At this point, I gave up trying to understand it all and, as seekers after enlightenment have done for centuries, travelled to ask the advice of the Buddha himself. ‘Master,’ I pleaded, prostrating myself before him. ‘Can you tell me: what is the spirit of Japan?’ Answer came there none. I think he just couldn’t hear me above the noise of his Walkman.